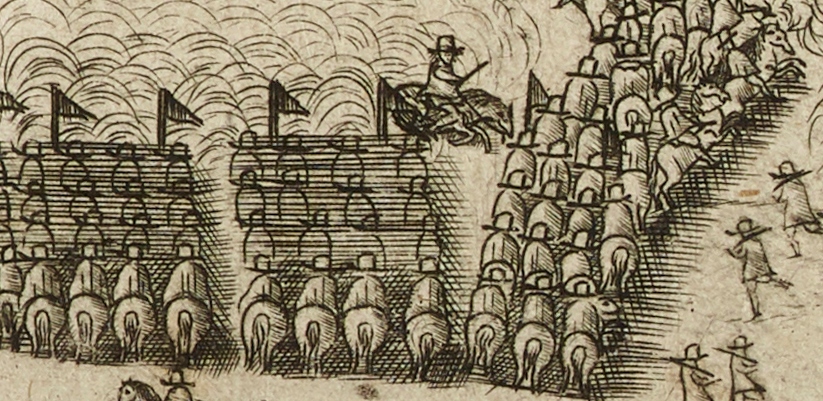

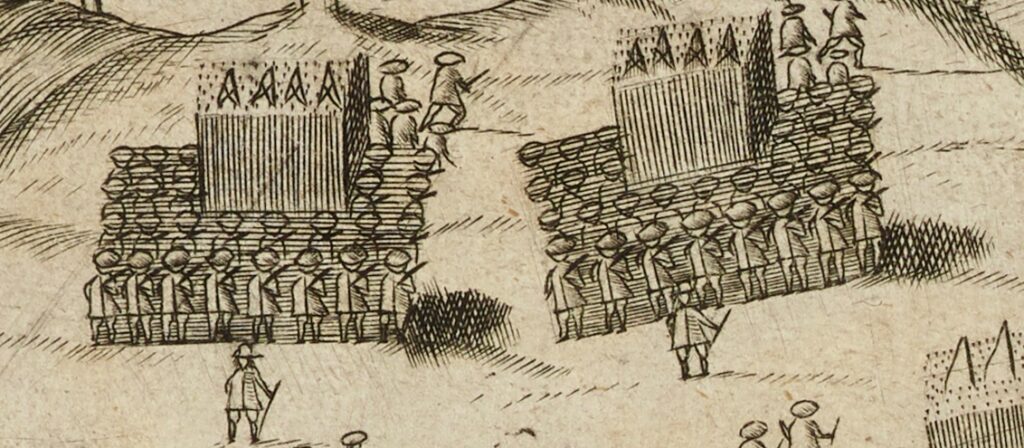

There was little difference between the two armies in terms of the types of weapons and formations they were trained to use. This was the age of pike and shot, combining the horrors of black powder warfare with the toils of physical combat, as soldiers formed into tight-packed bodies to contest control of the landscape. Large cavalry forces sought first to rout their counterparts, then turn decisively against any weaknesses in the infantry formations. Such battles took place over large areas, making them difficult to direct in detail. Battles could could be highly unpredictable, and a good general needed the skill – or good fortune – to be in the right place at the right moment.

By 1650, most of the English foot-soldiers were wearing red coats, the colour by which English (and later British) soldiers could be identified until the end of the 19th century. Most of the Scots wore hodden grey coats, commonly with round woollen bonnets. The muskets used were, except for a few exceptions, matchlocks. These required a length of burning match-cord to be kept by each man, and were problematic in weather as poor as the Dunbar campaign. Pikes could be up to 18ft in length, tipped with steel points. It took practice for large bodies of men to wield such weapons efficiently in unison, but they were effective not only at deterring cavalry but also in driving off other infantry. On both sides, armour was less common than it had been even just a decade before. The cavalry were armoured in a combination of metal and thick leather, the English equipment being far more heavy-duty than that of many of their lighter-armoured counterparts.

Regiments were divided into companies, and each company had a “colour”, a large flag which identified which unit was where. These were important markers and rallying points in battle and on the march. Scots colours generally bore the saltire, in a variety of colours, overlaid with the motto Covenant for Religion, King and Kingdoms (or an older variant). English colours tended to have a small cross of St George in the canton. Special colours for the colonel’s company commonly used devices from that officer’s personal heraldry. For battle, regiments were usually brigaded together to form larger formations known as battalia.

The Army of the Commonwealth of England

Commanded by Oliver Cromwell

Infantry: 7,500 fit for service; Cavalry: 3,500

Oliver Cromwell was an extremely able and experienced commander, who had risen to prominence fighting for the English Parliament in the Civil War. Since the execution of King Charles I, Cromwell had stormed through Ireland, turning the tide of years of stagnated warfare with brutal efficiency. The army he brought to Scotland in 1650 was well led and well motivated. At its core were veteran campaigners, united in their determination to prevent Scotland becoming a rallying point for the royalist cause they had fought so long to defeat. The infantry battalia were formed of pikemen and musketeers, whilst the cavalry were formidable armoured shock troops known as “ironsides”. There was also a small force of mounted infantry (dragoons), and a train of artillery to support the army in action. Despite their initial confidence, however, the failure to bring the Scots to battle quickly led to sickness and supply shortages, reducing the army’s initial strength by almost 5,000 men. When it entered Dunbar on 1 September, Cromwell’s army was facing the very real prospect of having to abandon the campaign regardless of whether the Scots could beat them in the field.

Order of Battle:

FOOT

Colonel George Monck’s Brigade: Monck’s Regiment; Mauleverer’s Regiment; Fenwick’s Regiment (5 co.)

Colonel Thomas Pride’s Brigade: Pride’s Regiment; Cromwell’s Regiment; Lambert’s Regiment

Colonel Robert Overton’s Brigade: Coxe’s Regiment; Daniel’s Regiment; Charles Fairfax’s Regiment

HORSE

Major-General John Lambert’s Brigade: Fleetwood’s; Lambert’s; Whalley’s

Colonel Robert Lilburne’s Brigade: Lilburne’s; Hacker’s; Twisleton’s

RESERVE

Cromwell’s Horse; Okey’s Dragoons

The Army of the Kingdom of Scotland

Commanded by David Leslie

Infantry: around 15,000; Cavalry: around 6,000

David Leslie was a professional soldier who had cut his teeth fighting in Europe even before civil war had broken out in Britain. When the Scots were still allied with the English Parliament, Leslie had fought at Cromwell’s side at the Battle of Marston Moor. Recalled to deal with the royalists in Scotland, he had then defeated the dreaded Montrose in 1645, cementing his reputation. Leslie’s army was large but mostly comprised fresh recruits. Some of his veteran officers had to be discharged because of suspected royalist sentiments, undermining the confidence and capacity of the army. Nevetheless, this was a large and capable army, which had performed well in checking Cromwell’s advance. As well as pikemen and musketeers recruited from right across Scotland, Leslie had a large force of cavalry. Many of these were lancers, lighter armed than their opponents but they had already proven their worth at Musselburgh and Haddington. With Cromwell’s army weakened, Leslie had every reason to believe he could beat it.

Order of Battle:

FOOT

Lt-General James Lumsden’s Brigade: Lumsden’s Regiment; General of Artillery’s Regiment; Douglas of Kirkness’ Regiment

Colonel James Campbell of Lawers’ Brigade: Lawers’ Regiment; Preston’s Regiment; Haldane’s Regiment

Maj-General Colin Pitscottie’s Brigade; Pitscottie’s Regiment; Home’s Regiment; Lindsay’s Regiment

Colonel John Innes’ Brigade: Innes’ Regiment; Forbes’ Regiment; Master of Lovat’s Regiment

James Holborne’s Brigade: Holborne’s Regiment; Buchanan’s Regiment; Stewart’s (Edinburgh) Regiment

HORSE

Adair of Kinhilt’s; Arnott’s; Brechin’s; Browne’s; Cassillis’; Riccarton’s; Erskine’s; Forbes’; James Hakett’s; Robert Hakett’s; Ker’s; Leslie’s; Leven’s; Mauchlines; Montgomery’s; Scott’s; Stewart’s; Strachan’s.